The world of fashion is (by design) a fast-moving place. From one season to another, the industry’s favoured materials, colors, and cuts can change incredibly unpredictably.

But the rise of Fast Fashion saw this pushed to extremes – suddenly, rather than the traditional four seasonal collections (reflecting differing weather conditions), some retailers were refreshing their stock with novelties up to 52 times a year.

It was part of a shift made possible by improved technology in the supply chain, but also a more cavalier attitude to workers’ rights and pollution. For a while, thanks to online retail and micro-trends mostly based on copying celebrities’ outfits, the model flourished. Some even predicted this would be the new normal.

But, with the news regularly dominated by stories rooted in accelerating climate change, concerns about how careless consumption might be contributing to this started to build – at first through unofficial blog posts, but soon picked up by the media.

Backlash Fashion

Soon, surveys were showing shoppers’ worries solidifying. In particular, 80% of Millennials across the UK, US – and even China – reported that the environmental impact of brands was increasingly a factor in whether they’d buy clothes from them (according to figures reported by Bonds).

Suddenly Fast Fashion didn’t seem as cheap as everyone thought. It’s just that the price was ecological, rather than financial. And the fashion industry – which traditionally tells its consumers what they should wear – was faced with a clear sign that brands would now be rated by their ethics as well as their designs. For them, it was a sobering moment.

Pioneers

The thing was, there were already clothing producers and retailers who had built such values into their brand from the beginning. People Tree is often cited among them, with a commitment to both Fair Trade (meaning decent pay for workers) plus organic materials since the Nineties.

Sustainable fashion must be at the heart of every designer.

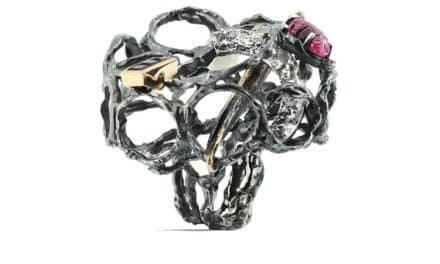

Since the turn of the millennium, there’s been an explosion of sustainable fashion. It’s now possible to get eco-friendly swimwear and skiwear, vegan ‘leather’, and even lab-grown diamonds.

Next Up

The only problem with the endless amount of sustainable start-ups is their size. Few have yet had time to grow into real rivals to the big players in the apparel business. Likewise, no matter how much the average consumer might want to buy greener clothing and accessories, the prices of more artisanal production can make it difficult.

These problems should fade as sustainable labels grow, streamlining their processes, and increasing their market share. But there are also real signs that most of the more traditional manufacturers have finally realised they can’t ignore environmental worries when their commercial rivals are outflanking them with younger shoppers. They’re also very aware of how quickly old-fashioned values can alienate tomorrow’s buyers.

And so, luxury brands will continue to edge further into sustainability. To be fair, given their capital and the prestige prices their items command they can absorb it better than most. The bigger difficulty will be faced by more mass-market producers and retailers.

Even here, though, it seems technology is increasingly offering solutions. Recycled materials are increasingly finding their way into sports shoes and hiking bags, for example – and 3D-printing is tipped to soon revolutionise wastage in the footwear industry.

All in all, it seems likely the ultimate decider of how clothing companies treat the planet – and their workers – lies in the hands of their consumers. So keep an eye on their record and only buy from those businesses willing to sacrifice a little profitability to be part of the solution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.