Ah, the world of eyewear, a domain where style meets utility and where the tag “Made In Italy” used to reign supreme. It’s me, a lover of all things luxurious and a bit of a fashion aficionado, if I do say so myself. Today, I’m diving into a topic close to my heart and my eyes – the transformation of eyewear production, particularly focusing on the Luxottica empire, from the Italian craftsmanship to the “Made in China” label.

Welcome to the world of eyewear Mafia.

The global eyeglasses industry was worth $105.56 billion in 2020, of which Luxottica controlled 80 percent. The company estimates that over half a billion people worldwide are currently wearing their glasses.

Made In Italy Was A Stamp Of Luxury

You see, there was a time when picking up a pair of sunglasses was not just about shielding your eyes from the sun; it was about embracing a piece of Italian heritage. I fondly remember my first encounter with a pair of Gucci sunglasses. Ah, those were the days when “Made In Italy” was a stamp of luxury, craftsmanship, and, let’s be honest, a bit of social status. But as I’ve come to learn, the tides have shifted, and so has the manufacturing of these opulent accessories.

Let’s talk about Luxottica, shall we?

The name itself conjures images of sleek designs and the kind of opulence that makes your heart skip a beat. Once, this giant was a beacon of Italian craftsmanship, a testament to what Made In Italy stood for. But as I sipped my espresso in a quaint café in Milan, a friend leaned in and whispered a truth that nearly made me spill my coffee – Luxottica’s latest collections, even those gorgeous 2024 Prada frames, are now proudly “Made in China.”

Luxottica has Prada license, Kering Eyewear has Gucci licence for eyeglasses and sunglasses.

Fiat

I’ll admit, I was taken aback. Not because I harbor any snobbery towards China’s manufacturing capabilities (they’ve proven themselves formidable in the fashion industry), but because it felt like a piece of Italy’s heritage was being sold off, piece by piece. Remember Fiat? Another Italian jewel now under French ownership. It seems Italy’s treasures are finding new homes, and it’s a bitter pill to swallow. I am wearing Gucci, 100% Made In China!

Milano

But let’s not dwell on the melancholy. After all, my love for fashion and eyewear isn’t dictated by geography. It’s the design, the story, and the swagger that a pair of sunglasses can bring to your ensemble that truly matters. I still cherish my trip to Milan, where I discovered an old school collector near the Duomo with an array of glasses that told stories of Italy’s past and present. He had frames that whispered secrets of designers from eras gone by, like the red baroque temple Prada frames I own, birthed from the imagination of a German girl who designed for Prada between 2009 and 2012. Ah, the narratives woven into those frames!

And let’s not forget Patty, the Oliver Peoples girl, who painted the world through her lenses before selling her vision to LVMH for a cool 80 million. These tales of creativity and transition from Italy to global stages are what fashion stories are made of.

Made in Italy to Made in China

Of course, the journey from “Made in Italy” to “Made in China” isn’t just about geography. It’s about the evolution of an industry that’s constantly seeking efficiency, innovation, and accessibility. The shift has ruffled some feathers, especially in Lombardy, where the line between craft smanship and mass production blurs. Suspicion and skepticism cloud the air as the definition of authenticity is challenged. Yet, amidst the uproar, there lies an undeniable truth – the essence of design and creativity knows no borders.

The Luxottica saga, with its roots stretching from the Sedico factory to the sprawling manufacturing hubs in Dongguan, China, is a testament to this global dance of design and production.

It’s a narrative that challenges purists but also opens up a dialogue about what luxury means in the 21st century.

Is it the stamp of origin, or the craftsmanship and design that defines luxury?

The World Of Fashion Is China

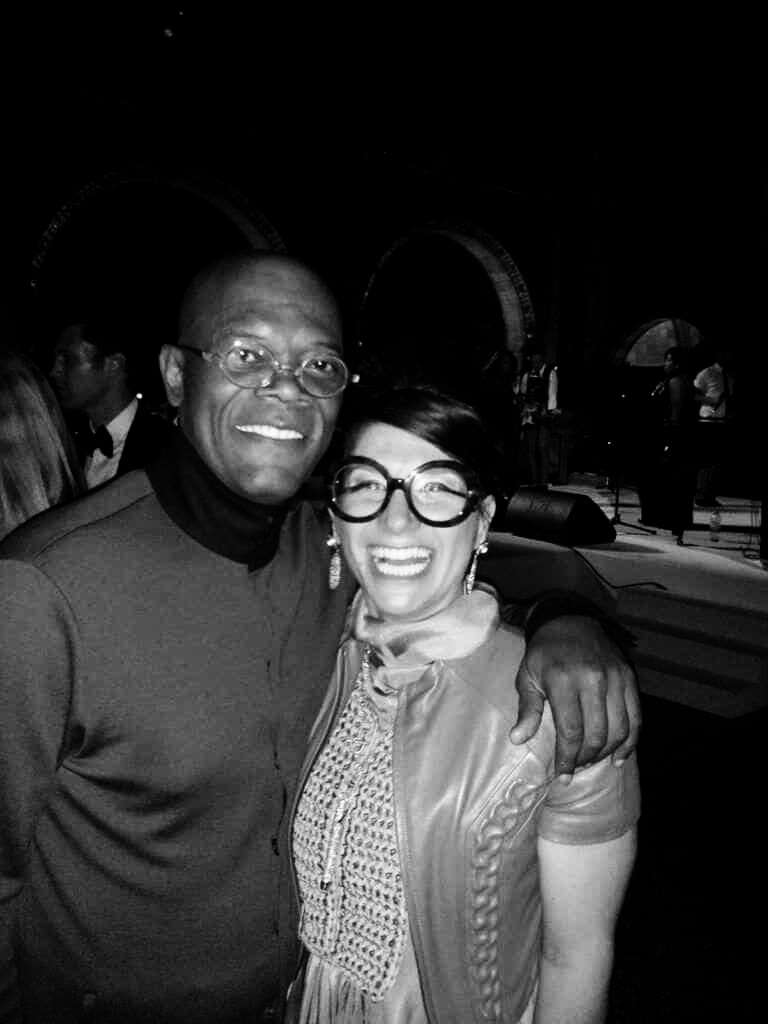

Expert eyewear owner, Sean Williams shares his views.

You must be logged in to post a comment.